Below are portions of the Montrose County Historic Landmark Application for Local Historic Register Designation, put together by Matthew Landt and the Montrose County Historic Landmark Advisory Board .

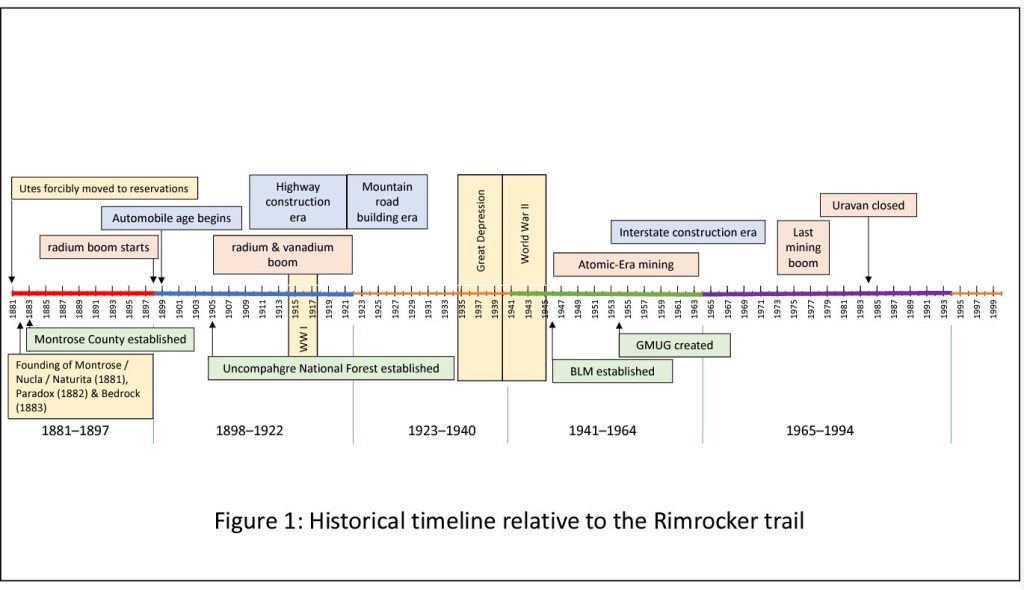

The Rimrocker Trail is an amalgamation of travel corridors made and used throughout the history of Montrose County (e.g., 1881–2000) and its significance lies not in any single section, but in the cumulative history of wagon and automobile travel that the Rimrocker Trail represents. In the following, that history is divided into five periods of historical significance (Image 1), those periods are defined by mapped road sections that are reflections of local and national historical events. The first period starts after the Ute are forcibly removed to reservations in 1881 and ends in 1897, before the radium boom in Montrose’s West End. The second period starts in 1898 with the West End’s radium boom and ends in 1922 with the end of the vanadium boom. The third period runs from 1923 – 1945 and encapsulates the Roaring 20s, the Great Depression, and World War II. The fourth period includes the post-war atomic era, and regional infrastructure expansion from 1946–1964. The final historical period covers the Cold War era from 1965–1994. Modern development and upgrading of the Rimrocker Trail continues as the route increases in popularity and further supports the economic development and growth of Montrose County. Further details of the historically significant periods of the Rimrocker Trail’s development can be found below.

Period of Significance 1 (1881–1897)

Approximately 2.1 mi. (2 percent) of the Rimrocker Trail first show up on early General Land Office maps during this period (see Map pages 6–7 and 9–10). This historical period begins with the forced removal of the Utes to reservations that allowed for the settlement of the area by Euroamerican farmers, ranchers, and miners. In 1881, Montrose, Nucla, and Naturita were founded with Paradox (1882), Bedrock (1883), and Montrose County (1883) following soon after. Most of the roads built in Montrose County during this time were built by privateers (e.g., Otto Mears and Dave Wood) and landowners as a means to access the vast forests, plateaus, and canyons of Montrose County. The 2.1 mi. of Rimrocker Trail associated with this period are either associated with a route leading from Nucla onto the Uncompahgre Plateau, mapped as “Wagon Road Paradox to Montrose,” or a section of road that crosses Coal Canyon. The Paradox to Montrose road, also known as the Old Paradox Road (Reed and Coreill 1991:site 5MN2991), was likely built immediately after the rush to use the San Miguel River drainage, Paradox Valley, and Horsefly area for grazing land. The Paradox to Montrose Road was then used to get cattle from Montrose’s West End to supply the military at Fort Crawford and to use the nearest railhead in Montrose for export (Mehls 1982:111–112). Later in time, this early road would be part of Colorado Route 97 between Nucla and Delta (Dobson-Brown and Autobee 2002). All of these 1881–1897 road sections follow original routes of horse-drawn wagons and predate the start of the automobile age (DobsonBrown and Autobee 2002).

Period of Significance 2 (1898–1922)

Roughly 21.1 mi. (20 percent) of the Rimrocker Trail appear on maps published during the radium and vanadium boom in the West End of Montrose County, World War I, the establishment of the Uncompahgre National Forest, and the start of the Automobile Age. “In 1898, Montrose County hosted one of the world’s first radioactive metals discoveries in the form of carnotite ore, which offered uranium, radium, and vanadium” (Twitty 2021:E1), making carnotite a new mineral discovery at a time when scientists were just beginning to study radioactivity. From 1910 and 1922, vanadium was being used in the steel industry, especially for military applications during World War I because it provides a hardening effect that increases the strength and welding performance of ordinary steel (Twitty 2021:E1). Ultimately, carnotite ore was used by scientists around the world, like Marie Currie, for its radioactive properties, the “medical industry also used it for revolutionary health applications” (Twitty 2021:E1), and vanadium was in demand during World War I, making the need to ship carnotite ore out of Montrose County one of national and world importance. This period also corresponds to the mass production of Henry Ford’s Model T, which was introduced in 1908 and began assembly line construction by 1914 (Dobson-Brown and Autobee 2002). Because of the automobile and growing automobile ownership, especially among the wealthy, the period from 1910–1920 was a period of large nationwide road building that was financially supported by the U.S. government with projected construction of Colorado Route 97 between Nucla and Delta (Dobson-Brown and Autobee 2002). The eastern end of the Rimrocker Trail (Map 1) represents road construction associated with the original Highway 90 (Map 1), and the bulk of the roads in this period near Nucla (Maps 8–11) are related to the growing economy of the West End and attempts to get carnotite ore to markets.

Period of Significance 3 (1923–1945)

No maps were published during this period, so it isn’t known if any portions of the Rimrocker Trail were built during the Roaring 20s, the Great Depression, or World War II. This period starts with the Quiet Years (1923–1934) of mining in the West End (Twitty 2021:E46), when radium and vanadium were being partially sourced outside of the U.S. Carnotite mining recovered during the Great Depression, as evidenced by the company town of Uravan that received a formal Post Office in 1936. Along with changes in mining during this period, the Model T became more affordable (e.g., $290 in 1924) and popular, which led to many roads being improved to handle the increased traffic (Dobson-Brown and Autobee 2002). Additionally, the Federal New Deal programs of the Great Depression utilized many Work Progress Administration (WPA) employees to build roads. Many of the Colorado WPA employees widened, graded, and resurfaced farm-to-market roads in rural areas (Dobson-Brown and Autobee 2002). As the U.S. entered WWII, President Roosevelt established an atomic weapons program in the hands of the Army Corps of Engineers as the Manhattan Engineer District’s Manhattan Project. Because the only viable domestic source of uranium and vanadium was in the Colorado Plateau, the Manhattan Project began attempts to find richer deposits in Montrose’s West End (Twitty 2021). The USGS and the U.S. Bureau of Mines sent geologists through the area to find ways to locate and recover uranium and vanadium. Although much of the initial work to source uranium and vanadium was done with large producers (e.g., Vanadium Corporation of American and the U.S. Vanadium Corporation), it was recognized that independent miners could produce significant amounts of ore if it could be consolidated at buying stations (Twitty 2021: E56–57). The U.S. government built roads in support of this effort, but once “the government had amassed enough uranium and vanadium by the middle of 1944, it suspended its purchase programs and effectively nullified the market for those metals” and created a local depression (Twitty 2021: E59–60). While roads were being improved and built during this period, the lack of maps from this period is likely a product of the Manhattan Project’s need for secrecy and national security, as well as being a product of the U.S. Geological Survey’s (USGS) internal processes. In 1882, John Wesley Powell, as Director of the USGS, acquired congressional authorization to create a series of uniform folios of individual quadrangles that included topography, geology, illustrations and text for the entire United States. Although never completed, that monumental effort created 227 individual quadrangle folios until the last one was published in 1945 (https://usgs.gov.programs/nationalcooperative-geologic-mapping-program/brief-hisotry-geologic-mapping-usgs, accessed November 16, 2023). Nineteen of the 227 quadrangle folios were made in Colorado, including Engineer Mountain, Ouray, Silverton, Rico, and Telluride, though none of the USGS’ focused effort was in Montrose County during this period.

Period of Significance 4 (1946–1964)

The bulk of the Rimrocker Trail (e.g., 70.7 mi., 65 percent) first appears on maps that immediately post-date World War II, though it is likely that some of these roads were built during the previous period of significance. This period of road growth includes the atomic era of mining in the West End, the establishment of the BLM (1946), and the merging of National Forests into the Grand Mesa, Uncompahgre, and Gunnison (GMUG) National Forest. Coming out of WWII, the U.S. government had no intention of stopping their nuclear program and created the Atomic Energy Commission (AEC). While vanadium was available on the open market for the steel industry and post-war consumerism, “the AEC commissioned the USGS with finding, understanding, and quantifying the uranium deposits” in the area (Twitty 2021:E61). The AEC used the USGS’ findings to reinvigorate the mining industry in the West End, which included the 1949 introduction and use of handheld Geiger counters and exposing photography film to samples to identify radioactivity by professional and weekend prospectors (Twitty 2021:E64). In 1956, the AEC stopped purchasing crude carnotite ore and shifted to purchasing processed yellowcake from mills, which increased the dominance of large companies and marginalized the smaller producers. A few years later AEC stopped purchasing processed yellowcake from new discoveries and eventually stopped guaranteeing prices and stopped exploration campaigns. The early 1960s were a period of slow decline for uranium and vanadium production that had a heavy effect on the economy of Montrose County. The exponential rate of ore production in the 1940s and 1950s led to growth in other areas of Montrose County and this period also encapsulates the growth and development of regional and interstate infrastructure (e.g., highways and transmission lines). After the deterioration of highways and gasoline rationing of WWII, tourism became Colorado’s third-largest industry, which also introduced the construction of interstates and the Freeway Era from 1941–1955 (Dobson-Brown and Autobee 2002). Although the National Forest’s Postwar Development Era (1946–1959) was largely focused on providing timber for an increasing consumer demand for wood products it also saw millions of new visitors and recreational demands (Williams 2005). Additionally, researchers started focusing on studies designed to find “ways to harvest trees, construct new roads, and measure the effects of logging and roads on streams and watershed” (Williams 2005:93), which also led to the use of new techniques in forest management that included pest control and fire containment. All of this eventually led to the Multiple-Use Sustained-Yield Act of 1960, which was supported by outdoor groups, the timber industry, the Forest Service, and Congress (Williams 2005). Because the period from 1946–1964 encapsulated the post-war push for uranium and vanadium in the West End as well as the growth of the timber industry and tourism across the Uncompahgre Plateau, the sections of the Rimrocker Trail are diverse in their historical use and incredibly significant as they relate to the historical economy of Montrose County.

Period of SignifiCance 5 (1965–1994)

Roughly 5.5 mi. (5 percent) of the Rimrocker Trail appear on Cold-War era maps. On the West End, the late 1960s and early 1970s was a period of troubled mining, where the recovered ore filled old contracts of the largest companies instead of going to the burgeoning nuclear power industry (Twitty 2021:E80). The total number of active mines plummeted as did the population and economy of the West End until 1974, when the nuclear power industry’s reliance on uranium became a strong alternative to the vagaries of international oil prices and oil embargos. While uranium prices surged in the late 1970s, mining companies began complying with increasingly strict waste disposal regulations, like the Uranium Mill Tailings Radiation Control Act (UMTRA) in 1978. Despite high uranium prices, many of the carnotite ore deposits bodies on the Colorado Plateau were exhausted and couldn’t compete with international mining efforts (Twitty 2021:E87). Compounded by the meltdown at Three Mile Island in 1979, the price of yellowcake fell dramatically and most of the mines in Montrose County were closed by 1981. The 1980s brought a shift from uranium production to environmental cleanup, especially of Uravan, which was known to be heavily contaminated with radioactive materials since the late 1970s. With Uravan closing in 1984 and the last resident removed in 1986, the communities of Nucla, Naturita, and Paradox “reverted to their ranching roots and turned toward tourism” (Twitty 2021:E88). Most of the highways and roads in Colorado had been built by the 1970s and mid-1980s, so work by the Colorado Department of Transportation (CDOT) focused on areas with the greatest traffic (Dobson-Brown and Autobee 2002). Because the rural and forested areas of Montrose County were best seen by automobile, much of Montrose County’s traffic was in the otherwise untouched mountains and canyons. Along with increased traffic, the 1970s saw the rise of the environmental movement, the desire of the public to keep National Forests pristine, and the 1969 National Environmental Protection Act. Although very few miles of the Rimrocker Trail were mapped during this time, the mapped sections in the West End from this period are important because they are essentially backcountry connections between abandoned mines and represent the transition from mining to the desire to see the natural beauty of Montrose County.

Period of Significance 6 (Modern post-1994)

These 8.7 mi. (8 percent) of the Rimrocker Trail are essentially modern roads. The 1990s saw increased tourism in the rural areas of Montrose County, which brought increased traffic and larger vehicles, both industrial (e.g., logging trucks) and recreational (e.g., SUVs and luxury cars). With the increased traffic came a need to maintain roads. Most of the road segments that were initially mapped in this period connect older road segments by either straightening older curves to handle modern vehicles or by widening curves to handle multiple lanes of increased traffic. While not historical in the same way as other Periods of Significance, these road segments are important because they represent modern use of the Rimrocker Trail and its continued importance as a connecting route across Montrose County.

Read more about the Historic Landmark Advisory Board.

See the Montrose Board of County Commissioner meeting where the Rimrocker Trail was approved as a historic landmark on 4/17/24.